The true worth of a fine timepiece lies not in its marketing, but in its verifiable mechanical integrity and invisible artistry.

- Hand-finishing, invisible to the naked eye, can represent hundreds of hours of manual labour and is the primary driver of value.

- Practical complications like a GMT or annual calendar offer more daily utility for a UK professional than purely decorative ones.

Recommendation: Before investing, learn to look for the hallmarks of quality yourself—like sharp internal angles on a movement—rather than relying on a brand’s reputation alone.

For the discerning individual, the decision to acquire a ‘serious’ watch marks a significant milestone. It’s a statement of taste, an appreciation for engineering, and often, a future heirloom. Yet, stepping into a Bond Street boutique can feel like entering a foreign land. You are met with a barrage of technical jargon—tourbillons, anglage, Poinçon de Genève—that seems designed to obscure rather than illuminate. The line between a genuinely exceptional timepiece and a merely expensive, mass-produced luxury item becomes frustratingly blurred. Many guides will tell you it’s about “craftsmanship” or “complications,” but they rarely explain what that truly means in tangible terms.

The common advice is to trust the big brand names or the hefty price tag as indicators of quality. But this approach is flawed. It makes you a passive consumer, reliant on marketing, rather than an informed collector who understands the intrinsic value of what is on their wrist. What if the secret to identifying true haute horlogerie wasn’t about memorising brand hierarchies, but about understanding a core set of principles? What if you could learn to see the difference for yourself?

This article is designed to be your guide through that maze. We will move beyond the marketing gloss to focus on the verifiable markers of fine watchmaking. We will deconstruct why hand-finishing is so costly, assess which complications genuinely add value to a modern British lifestyle, and decode what prestigious certifications actually guarantee. By the end, you won’t just be buying a watch; you will be investing in a piece of mechanical art, armed with the knowledge to make a truly confident choice.

To navigate this complex world, this article breaks down the essential pillars of fine watchmaking. The following sections will equip you with the insights needed to distinguish a masterpiece from a simple luxury product, empowering you to become a true connoisseur.

Summary: The Connoisseur’s Guide to Understanding Fine Watchmaking

- Why Hand-Finishing Can Double the Price of a Watch Movement?

- Which Watch Complications Actually Add Value to Your Daily Routine?

- What Does the Poinçon de Genève Mean for the Longevity of Your Watch?

- How the Evolution of Fine Watchmaking Influenced Modern British Style?

- Silicon vs Traditional Hairsprings: Which Is Better for Magnetic Resistance?

- Why Independent Swiss Brands Are the New Status Symbol in The City?

- Why Does It Take Nine Months to Assemble a Single Grand Complication Movement?

- Why Do Minute Repeaters Cost More Than a House in Some Parts of the UK?

Why Hand-Finishing Can Double the Price of a Watch Movement?

The single greatest differentiator between a luxury watch and a work of haute horlogerie is the human hand. While a machine can produce a technically perfect component, it cannot impart the artistry, precision, and soul that comes from hand-finishing. This is not mere decoration; it is a rigorous discipline that enhances a movement’s beauty, longevity, and performance. Techniques like black polishing (specular polish), where a steel surface is polished so perfectly it appears black from certain angles, or anglage (bevelling), where sharp edges of components are filed and polished to a mirror shine, are incredibly time-consuming. These details are often hidden inside the case, known only to the owner and the watchmaker.

The economic impact is staggering. This “invisible artistry” is what separates a £10,000 watch from a £100,000 one. For instance, a masterpiece like the Romain Gauthier Logical One requires over 90 hours of finishing for the movement components alone. This level of dedication is exemplified by artisans like Philippe Dufour, widely considered the king of finishing. His Grande et Petite Sonnerie, a masterpiece of hand-work, became the most expensive wristwatch ever sold publicly by an independent watchmaker, proving that the market places immense value on this manual expertise. For the aspiring connoisseur, learning to spot these details is the first step towards understanding true value.

Your Checklist for Spotting Genuine Hand-Finishing

- Component Edges: Look for uniform grain and mirror-bright bevelled edges (anglage) on the movement’s bridges and plates, with no machine ‘chatter’ or tool marks.

- Screw Heads: Examine screw heads under a loupe. They should have crisp, clean slots and polished chamfers, sitting perfectly flush with the surface.

- Steel Parts: Check for true black polish on steel parts. When tilted slightly, the surface should appear jet black, a sign of perfect flatness that machines cannot replicate.

- Internal Angles: The hallmark of true hand-finishing is the presence of sharp, inward-pointing angles on bevelled edges. A machine can only create rounded internal corners.

- Overall Consistency: Inspect the width and shine of the anglage along all edges. Hand-execution results in a consistent, mirror-like finish that flows beautifully.

Which Watch Complications Actually Add Value to Your Daily Routine?

In watchmaking, a ‘complication’ is any function on a watch that does more than tell the time. While horologists celebrate the complexity of tourbillons and minute repeaters, the aspiring owner should ask a more practical question: which of these features provide genuine, tangible utility? For a professional in the UK, not all complications are created equal. The key is to separate the truly useful from the poetically beautiful but functionally niche.

A chronograph, for example, is essentially a stopwatch. While often associated with motorsport, its practicality in daily life is immense—timing a commute, a presentation, or even a parking meter. A GMT or Dual Time function is indispensable for anyone working in London’s global financial sector or who travels frequently, allowing them to track two time zones at once. An Annual Calendar, which only needs adjusting once a year, offers most of the convenience of a Perpetual Calendar at a fraction of the cost and complexity. Conversely, a beautiful Moonphase complication has limited practical use under the UK’s often overcast skies. The ultimate decision is personal, but it should be informed by an honest assessment of one’s lifestyle, not just the technical prestige of the complication.

The following table provides a pragmatic breakdown of the most common complications, contextualised for a professional based in the UK, helping to distinguish daily value from horological novelty.

| Complication | Daily Utility | UK Context Value | Maintenance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMT/Dual Time | High | Essential for London finance professionals | Minimal added service cost |

| Annual Calendar | Medium-High | 90% of perpetual calendar convenience at 50% price | Service every 5-7 years |

| Chronograph | Medium | Timing commutes, meetings, parking | Higher service costs |

| Moonphase | Low | Limited use under UK’s overcast skies | Requires periodic adjustment |

| Power Reserve | High | Daily peace of mind for watch rotation | No additional maintenance |

What Does the Poinçon de Genève Mean for the Longevity of Your Watch?

The Poinçon de Genève, or Geneva Seal, is one of the most prestigious certifications in watchmaking. Established in 1886, it is a standard of excellence awarded only to timepieces assembled and regulated within the Canton of Geneva that meet a strict set of criteria for finishing and performance. A watch bearing the Seal is guaranteed to have a movement where every single component, visible or not, is finished to an exceptionally high standard. This includes decorative patterns like Côtes de Genève, polished screw heads, and perfectly executed anglage. For the owner, this is more than an aesthetic guarantee; it is a promise of mechanical integrity. Well-finished parts create less friction, suffer less wear, and are more resistant to corrosion, directly contributing to the watch’s accuracy and longevity over decades.

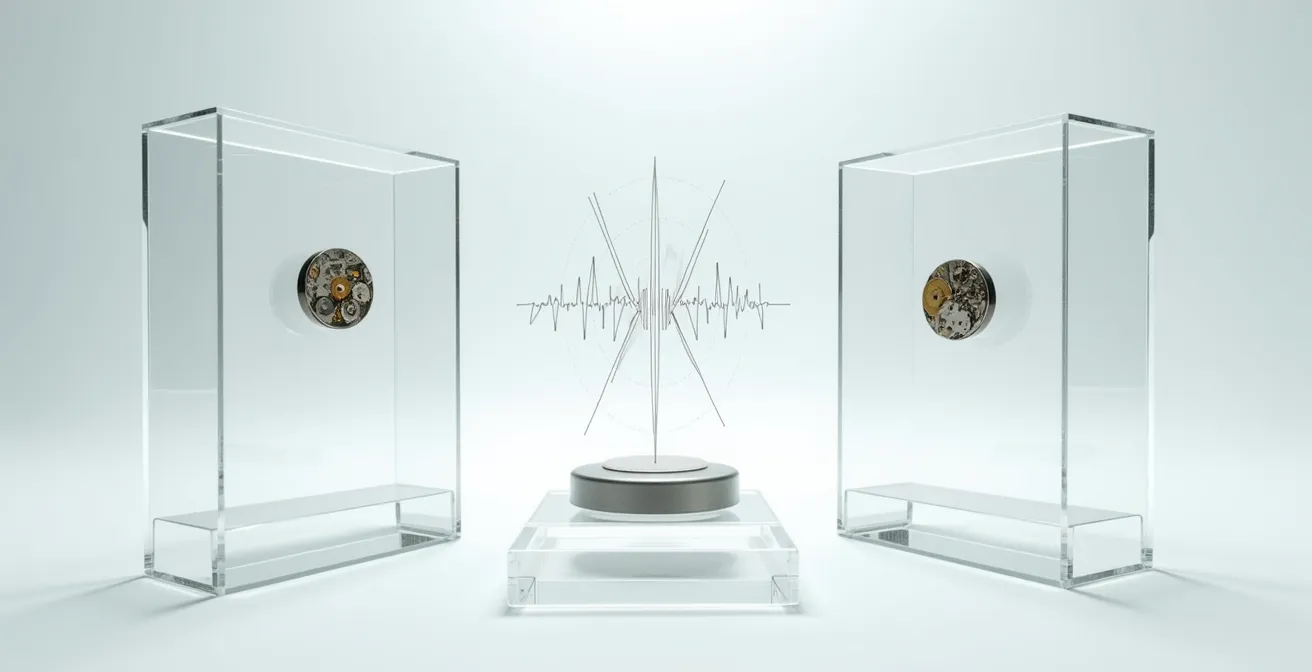

This image provides a glimpse into the world of certified movements, where raw metal is transformed into a work of mechanical art, meeting the stringent quality criteria that ensure its endurance.

However, it’s crucial to understand that the Geneva Seal is not the only hallmark of quality. Its geographical limitation means that some of the finest watchmakers in the world, based in Germany or other parts of Switzerland, are ineligible. For example, the German maison A. Lange & Söhne is renowned for its superlative movement finishing, so much so that even Philippe Dufour declared they make the world’s best chronographs. This demonstrates that while the Geneva Seal is a powerful indicator of quality, the ultimate assessment should be based on the principles of fine finishing itself, which can be found in watches with or without the prestigious stamp.

How the Evolution of Fine Watchmaking Influenced Modern British Style?

While the heart of traditional haute horlogerie beats in the Swiss valleys, its influence on modern British style is undeniable. For generations, a fine watch has been an essential part of the well-dressed Briton’s wardrobe, a subtle nod to quality and discernment peeking from under a shirt cuff on Savile Row or in a City boardroom. Historically, this meant a classic dress watch from an established Swiss maison. Today, however, the landscape is changing, reflecting a broader shift in British luxury towards a more individualistic and informed approach. The UK’s taste in watches has matured beyond simple brand recognition.

This growing sophistication is driving a vibrant market, with projections showing the UK luxury watch market is projected to reach USD 1.85 Billion by 2034. This growth is fuelled by a new generation of buyers who value craftsmanship and design innovation as much as heritage. A perfect example of this new dynamic is the British brand Christopher Ward. By designing its watches in Britain and having them assembled to high standards in Switzerland, the brand offers a taste of haute horlogerie at a more accessible price point. Their C1 Bel Canto, a complex chiming watch, sold out its initial run of 300 pieces in hours, demonstrating a powerful appetite among UK consumers for watches that offer exceptional value and a compelling story, disrupting the traditional model.

This trend shows that British style is no longer just about importing Swiss tradition. It is about a confident fusion of global craftsmanship with a distinctively British design sensibility and an astute eye for value. The ‘right’ watch is no longer just the most famous one, but the one that best reflects the owner’s personal taste and deep appreciation for the craft.

Silicon vs Traditional Hairsprings: Which Is Better for Magnetic Resistance?

At the very heart of a mechanical watch is the regulating organ, a delicate dance between the balance wheel and the hairspring. The hairspring is a minuscule, coiled spring that provides the oscillating force, effectively acting as the heartbeat of the movement. For centuries, this component was made from metal alloys like Nivarox. However, the modern world, filled with magnets in smartphones, laptops, and speakers, poses a significant threat to these traditional movements. Magnetism can cause the coils of a metal hairspring to stick together, making the watch run erratically fast. This is where one of the most significant innovations in modern watchmaking comes in: silicon.

Silicon (or ‘silicium’ in industry parlance) is a glass-like material that is completely amagnetic. A watch fitted with a silicon hairspring is virtually immune to the magnetic fields we encounter in daily life. Furthermore, silicon can be manufactured with a level of precision that is impossible with metal alloys, leading to improved chronometric stability. This has sparked a fierce debate among purists: the romance and repairability of a traditional metal hairspring versus the superior performance and resilience of modern silicon. There is no right answer, but it highlights a key consideration for a modern buyer.

This image illustrates the fundamental difference in how these materials behave under magnetic influence, showcasing silicon’s clear technical advantage in ensuring reliable timekeeping in today’s environment.

For someone seeking a robust, everyday timepiece that requires minimal fuss, a watch with silicon components offers undeniable practical benefits. For the traditionalist who values classical watchmaking and the idea of a watch being repairable by any skilled watchmaker a century from now, a traditional alloy may hold more appeal. It is a choice between cutting-edge performance and timeless tradition.

Why Independent Swiss Brands Are the New Status Symbol in The City?

For decades, the ultimate status symbol on a wrist in the City of London was a watch from one of the “holy trinity” of Swiss brands. It was a clear, unambiguous signal of success. Today, a quieter but more profound revolution is taking place. A growing number of discerning collectors are turning away from the mainstream and towards independent watchmakers. These small-scale artisans, often producing fewer than a hundred watches a year, offer something the big brands cannot: rarity, a direct connection to the creator, and a focus on pure horological art over marketing. Owning a piece from a creator like F.P. Journe, Kari Voutilainen, or Akrivia is a statement of deep knowledge, a signal to those ‘in the know’.

This trend is particularly strong in London, where an appetite for sophisticated luxury is deeply ingrained. A recent study shows that 22% of London residents plan to purchase a luxury watch between 2023-2025, compared to 13% nationally, and a significant portion of this discerning market is looking for uniqueness. The rise of independents is being recognised even by the luxury establishment. In 2024, Spanish watchmaker Raúl Pagès, who honed his craft restoring pieces for Patek Philippe, won the inaugural LVMH Independent Creatives prize. This kind of validation from a major luxury conglomerate confirms that independent creators are no longer on the fringe; they are setting the new standard for exclusivity and creativity.

For the City professional, choosing an independent brand is the new power move. It suggests that the owner’s status is not reliant on a famous logo, but on their own taste and ability to recognise genius and artistry. It is a shift from conspicuous consumption to connoisseurial appreciation, and it is the ultimate modern status symbol.

Why Does It Take Nine Months to Assemble a Single Grand Complication Movement?

The term ‘Grand Complication’ refers to a watch that contains multiple high-level complications, typically including a perpetual calendar, a chronograph, and a minute repeater. To assemble such a timepiece is considered the pinnacle of a watchmaker’s career. The timeline, often stretching to nine months or more for a single movement, can seem abstract, but it is rooted in a painstaking process where there are no shortcuts. It is a testament to the extreme level of human skill and patience required.

The process is not a simple assembly line. It is an iterative cycle of construction, testing, disassembly, adjustment, and reassembly. Hundreds of microscopic parts—levers, springs, gears, and screws—must not only be finished to perfection but also work in perfect, synchronised harmony. A minute repeater’s striking mechanism, for example, has to be tuned by ear, with the master watchmaker painstakingly filing the gongs to achieve the perfect pitch. This fusion of high-precision engineering and artisanal touch is what consumes so much time. A simplified breakdown of this nine-month journey reveals the immense dedication involved:

- Months 1-2: Pre-assembly, which involves the individual hand-finishing and preparation of over 600 separate components.

- Month 3: Assembly of the base movement and conducting the first phase of regulation for timekeeping accuracy.

- Months 4-5: Meticulous installation and integration of the complex complication modules, such as the perpetual calendar and chronograph mechanisms.

- Month 6: Assembly of the intricate striking mechanism for the minute repeater, the most delicate part of the process.

- Month 7: Fine adjustment and the critical synchronisation of all complications to ensure they function together flawlessly.

- Month 8: Casing the completed movement, followed by final regulation and rigorous testing to chronometer standards.

- Month 9: An extended period of testing the finished watch under various temperatures and positions, followed by the final, exhaustive quality control.

This journey from raw components to a finished masterpiece is what defines the exclusivity of a grand complication. It is a process where time is the most valuable ingredient.

Key Takeaways

- True value in watchmaking comes from verifiable skill (hand-finishing, complex assembly), not just brand prestige.

- The most valuable complications are those that offer tangible utility to your specific lifestyle, not just technical complexity.

- The rise of independent watchmakers offers a new form of status based on connoisseurship and rarity over mass-market recognition.

Why Do Minute Repeaters Cost More Than a House in Some Parts of the UK?

Of all the grand complications, the minute repeater is often considered the most challenging and revered. It is a miniature mechanical marvel that chimes the time on demand—hours, quarter-hours, and minutes—using a complex system of racks, snails, and hammers striking tiny, tuned gongs. The cost of these timepieces regularly runs into hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of pounds, a figure that can be difficult to comprehend. How can a watch cost more than a substantial family home? The answer lies in a confluence of extreme skill, immense time, and near-obsolete artistry. As the Chrono24 editorial team notes, the level of expertise required is astronomical.

Mastering the assembly of any single one of the complications from this selection can take a watchmaker years, let alone creating one from scratch, so the Grand Complication is reserved for those rare few that have gained both the knowledge and the skills required.

– Chrono24 Editorial Team, What is Haute Horlogerie?

A minute repeater movement can contain over 400 parts, many no bigger than a grain of sand, all of which must be assembled and adjusted by a single master watchmaker. This process can take over 300 hours of focused work. The ‘tuning’ of the gongs is an art form in itself, relying on the watchmaker’s ear, not a machine. This concentration of hundreds of hours of a rare, highly specialised skill into a single object is the primary driver of its cost. When you buy a minute repeater, you are not just buying a watch; you are commissioning a unique work of art from one of the few masters on earth capable of creating it. To put this into perspective, comparing the price of these horological masterpieces to the UK property market provides a stark illustration of their value.

| Item | Price Range | What It Represents |

|---|---|---|

| Entry-level Minute Repeater | £150,000-250,000 | 2-bedroom house in North East England |

| Mid-tier Grand Complication | £250,000-500,000 | 3-bedroom house in Manchester |

| Top-tier Minute Repeater | £500,000-1,000,000 | 4-bedroom house in Surrey |

| Ultra-exclusive piece | £1,000,000+ | Luxury flat in Mayfair, London |

Ultimately, distinguishing true haute horlogerie is an education in appreciating what lies beneath the dial. It is about shifting your focus from the brand name on the front to the mechanical soul ticking within. By learning to recognise the hallmarks of elite hand-finishing, understanding the practical value of complications, and appreciating the immense human skill invested in a movement, you transform from a consumer into a connoisseur. The next time you consider a serious watch, your first step should be to ask for a loupe, not a catalogue.